Vaccine hesitancy (aka anti-vaxxing) is now identified by the World Health Organization as one of the ten greatest global health threats. Global vaccine hesitancy rates average near 30%. While these statistics paint a concerning picture, the lived experience of working in healthcare settings where vaccine-preventable diseases remain prevalent reminds me daily of the privileged position of vaccine hesitancy.

Personal Encounters with Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

As a fourth-year medical student, I studied in Nepal at Kanti Children’s Hospital. A lone American, I learned alongside the brilliant local trainees. I was given special privileges, taken to meetings where the brightest minds tried to strategize on the cases of the day. These experiences not only shaped my medical education but provided me with a global health perspective that many of my peers in the United States lacked.

On my way through the hospital everyday, I walked past the Tetanus Ward. Yes, that was the ward where all the babies dying of tetanus were cared for. You’ve never seen a Tetanus Ward in the US, because tetanus is vaccine preventable. This direct exposure to preventable suffering established a foundation for my understanding of vaccine importance that no textbook or lecture could have provided. Global research confirms that direct experience with vaccine-preventable diseases significantly impacts healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward vaccination, with those having witnessed disease complications being more likely to strongly recommend vaccines.

In the outpatient clinics, where hundreds of people were queued up prior to the opening, I would be quizzed, “This child has fever, rash and conjunctivitis. What is your top diagnosis?” Kawasaki Disease, of course! That was easy. I had seen plenty of cases of Kawasaki. Nope, it was measles. I had never seen a case of measles before. That first day in the clinic in Kathmandu, I saw dozens. The measles I encountered in Nepal is the same virus that causes over 100,000 deaths annually, even to this day, primarily among young unvaccinated children, despite the availability of a safe and effective vaccine.

The Paradox of Vaccination Success

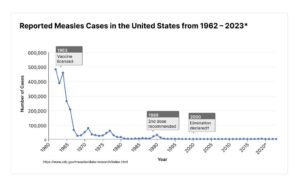

The fact we are at all having a national discussion over measles is a problem of the scientific community’s success. We no longer see these diseases in horrific numbers and they become easy to ignore. We feel immune, not realizing we are basking in the success of vaccines. Systematic reviews have identified this phenomenon of complacency as one of the major contributors to vaccine hesitancy, particularly in high-income countries where the memory of devastating outbreaks has faded.

In the early 2000s, not that long ago, when I was in training, I did spinal taps on babies routinely. Why? Anytime an infant had a fever, we had to make sure the baby did not have a life-threatening meningitis. Now, pediatricians do not learn how to do these procedures because of successful vaccination campaigns. Those forms of meningitis are now so rare that most current trainees rarely see a case of pneumococcal or haemophilus meningitis. This is a good thing… until we have enough parents who stop vaccinating and these diseases re-emerge.

The Luxury of Hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy represents a luxury that exists primarily in contexts where the horrors of vaccine-preventable diseases have faded from collective memory. When I discuss vaccines with hesitant parents in the United States, I often hear concerns that would be considered luxuries in many parts of the world. While parents in some parts of the world desperately seek protection for their children against diseases known to cause harm, parents in affluent communities worry about theoretical long-term consequences that have no scientific basis. How much money have we already wasted de-bunking the link between vaccines and autism?

Public Health Parallels and Safety Measures

When I was born, seatbelts and carseats were optional. Then we learned, through research, that seatbelts and carseats actually save lives. Following this, laws were made to turn this knowledge into applied behaviors, because people were not changing their behaviors based on new information. Similarly with alcohol use, laws were made to prevent people from getting behind a wheel when they drink. When it comes to public health, vaccinating yourself or your loved ones is putting on your seatbelt and making sure they, too, are properly restrained.

I am often asked about long-term sequelae of vaccines. I always give this answer: For nearly 100 years, we have been vaccinating people and when vaccines have side effects, we see them within 6 weeks. When we have wild type infections (like you go out and catch the bug), the case is different. After measles, you may develop subacute sclerosing panencephalitis up to 10 years after your measles infection. This is a devastating neurological condition starting with a decline in cognitive and motor skills, like grades getting worse or coordination problems, eventually resulting in seizures, a vegetative state and death. There has never been a case of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis after the measles vaccine.

Next steps?

While systematic reviews have found that scientists themselves are not immune to vaccine hesitancy, rates among healthcare professionals are lower than in the general population. Now we also know that social media spreads vaccine misinformation and 80% of scientists support social media regulations to prevent misinformation. That does not look like it will happen so, again, we must rely on public health efforts which, for the time being, are not working in my favor. Meanwhile, anti-vaxxing has consequences. The 2019 U.S. measles outbreak cost $3.4 million and that was only 72 cases!

So now what? I know I am not going to change anyone’s mind with statistics. If you are reading this, you probably already vaccinated your kids against childhood diseases. Arguing in favor of vaccines or presenting data never helped me get parents to vaccinate, but when I asked them what they were worried about, I eventually could meet them in a place of mutual understanding. Next time you are in a conversation with someone you disagree with, ask them why they are afraid of vaccines. Showing interest and coming from a place of true curiosity will get you much further. Spewing facts will only make the other party dig in deeper.

Vaccine hesitancy is a byproduct of prosperity—a privilege unavailable where children still die routinely of vaccine preventable diseases like tetanus and measles. As I witnessed in Nepal, these diseases aren’t historical footnotes but present-day realities. Science has given us a magical tool– we actually eliminated measles in the US 25 years ago! But we are letting our successes steer us backward. Just as seatbelts protect all occupants during a crash, vaccines shield communities. Let’s not unravel decades of progress for theories without evidence.

https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

Romate, John et al. “What Contributes to COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy? A Systematic Review of the Psychological Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy.” Vaccines vol. 10,11 1777. 22 Oct. 2022, doi:10.3390/vaccines10111777

McCready, Jemma Louise et al. “Understanding the barriers and facilitators of vaccine hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccine in healthcare workers and healthcare students worldwide: An Umbrella Review.” PloS one vol. 18,4 e0280439. 12 Apr. 2023, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280439

https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

Rocke Z, Belyayeva M. Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis. [Updated 2023 May 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560673/

Welch, Eric W et al. “How Scientists View Vaccine Hesitancy.” Vaccines vol. 11,7 1208. 6 Jul. 2023, doi:10.3390/vaccines11071208

Pike, Jamison et al. “Societal Costs of a Measles Outbreak.” Pediatrics vol. 147,4 (2021): e2020027037. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-027037